Richmond signs off, reporter reflects

May 30, 2008

If I was having pangs of regret over my decision to leave the broadcasting industry, all doubt was erased last week.

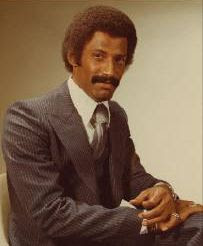

Longtime KTVU anchor Dennis Richmond retired after 40 years of delivering local and national headlines to San Francisco Bay Area residents. I grew up watching and idolizing the iconic journalist. He is the quintessential newsman: he's got all the smarts and wit to know a good story when he sees one, but without the frivolous bells and whistles and matching ties and hankies and insipid banter local news is so racked with these days.

Richmond gave you the facts and he gave it to you straight. There was nary a glimmer in his eye, not the faintest crack of a slight smile when he told you about the fundraiser for homeless children. He didn't artificially emote when he gave you updates on the fatal highway shooting. Richmond told you the news exactly as it happened. He let you decide where you would stand on the issues. I will always appreciate that.

But after nearly four decades of telling it like it is, Richmond announced his retirement early this year. He signed off for one last time on Wednesday, May 21, 2008.

I was back in the Bay Area just in time for Richmond's last newscast. I knew I wanted to catch this final goodbye. I also knew I had dinner plans that night. What's a girl to do?

Enter TiVo. And YouTube. And a host of other online sites that captured the poignant moment.

I caught the last hoorah on my TiVo, zipping through commercials and the blood and guts at the top of the hour. I logged on to YouTube, filtered out all the other noise and watched the handful of segments that interested me in this man's career. It is ironic that I now get my information from someplace other than the television, considering I spent the better part of my adulthood working in the television news industry.

And then it hit me. I am not alone. This generation receives its information in e-mails, on iPhones. People are not waiting around for the evening newscast to find out what's going on with the world.

Richmond's sign-off, in many ways, signals the end of an era, both for me and the industry. He is the last of his kind. The all-knowing, authoritative voice of God that boomed into your living room at 6 p.m. sharp. Overseas disasters, soaring fuel prices, a plummeting economy--my parents and their parents depended on these men and women to understand the world. Today, I have Google, ready at the click of a mouse whenever and wherever I want or need it.

I am grateful I worked briefly with Richmond in the early years of my broadcast career. While I was an intern at KTVU, Richmond treated me with respect. He was extremely knowledgeable, approachable and caring. He wanted young people to succeed. He gave me tips on how to do it right. The way he'd done it right for four decades.

True journalism, the kind Richmond delivered, may get buried in the hustle and bustle of high tech as the Internet continues to revolutionize information flow and, hence, the news industry. But, to this perpetual reporter and storyteller at heart, true journalism, the kind Richmond delivered, will never be forgotten. I will always have YouTube to remind me.

>>> Back to The World of Catze homepage <<<

Labels: broadcast television news, Catherine Mylinh, Dennis Richmond, Google, information, Internet, KTVU anchor, technology, TiVo, YouTube